| Welcome to Sprocket School! This project is maintained by volunteer editors. Learn more about how this works. |

Platter Systems: Difference between revisions

JesseCrooks (talk | contribs) No edit summary |

JesseCrooks (talk | contribs) m Removed duplicate link |

||

| (9 intermediate revisions by 2 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

[[File: | [[File:Strong platter system.jpg|right|thumb|400px|A Strong platter system.]] | ||

A platter system is a non-rewind film transport system in which multiple reels are [[splicing|spliced]] together on a horizontal deck. Each platter deck can hold enough film to allow all but the longest features to play without a changeover or intermission. The film is fed through a centerfeed, run through the projector, and wound onto a center ring on the takeup platter. To play the film again, the ring is removed and the film is rethreaded through the centerfeed, allowing it to be run repeatedly without being rewound. | A platter system is a non-rewind film transport system in which multiple reels are [[splicing|spliced]] together on a horizontal deck. Each platter deck can hold enough film to allow all but the longest features to play without a changeover or intermission. The film is fed through a centerfeed, run through the projector, and wound onto a center ring on the takeup platter. To play the film again, the ring is removed and the film is rethreaded through the centerfeed, allowing it to be run repeatedly without being rewound. | ||

==History and Use== | ==History and Use== | ||

[[File:Plattered print.jpg|right|thumb|400px|A plattered print being clamped for transport.]] | |||

Platter systems rose to popularity in the late 1970s as part of the movement towards increased [[automation]]. Along with the transition from [[carbon arc]] to [[xenon short-arc lamp|xenon lamps]] and the development of [[automation system|automation control systems]], platter systems facilitated the rise of the [[multiplex]] (a movie theater with several screens). Platter systems and other single-reel film transport systems such as towers and double make-up tables (MUTs) largely replaced reel-to-reel projection as the most common means of [[35mm]] projection because it enabled the simultaneous screening of multiple films on multiple screens with fewer operators. Benefits of the platter system included reduced labor costs—multiple films could be run simultaneously by a single projectionist or theater manager—and reduced print wear over the course of a long run. After the reels have been plattered the projectionist only handles the clear leader spliced to the head and the tail of the last reel, and the print does not have to be rewound between each screening. | Platter systems rose to popularity in the late 1970s as part of the movement towards increased [[automation]]. Along with the transition from [[carbon arc]] to [[xenon short-arc lamp|xenon lamps]] and the development of [[automation system|automation control systems]], platter systems facilitated the rise of the [[multiplex]] (a movie theater with several screens). Platter systems and other single-reel film transport systems such as towers and double make-up tables (MUTs) largely replaced reel-to-reel projection as the most common means of [[35mm]] projection because it enabled the simultaneous screening of multiple films on multiple screens with fewer operators. Benefits of the platter system included reduced labor costs—multiple films could be run simultaneously by a single projectionist or theater manager—and reduced print wear over the course of a long run. After the reels have been plattered the projectionist only handles the clear leader spliced to the head and the tail of the last reel, and the print does not have to be rewound between each screening. | ||

| Line 26: | Line 27: | ||

These methods of marking reel changes are completely unnecessary for two reasons. First, platter houses used colorful [[splicing tape|zebra tape]] to delineate reel changes, so a projectionist rewinding at a responsible speed would be able to find the splice without an issue. Second, reel changes are visible on the platter. The splices themselves can usually be found (they are thicker than the surrounding film), and it is possible to differentiate between reels because the surface of each reel has a slightly different gloss (just as trailers joined on a reel can be distinguished by viewing the side of the reel). Although film that was printed separately and joined with an ultrasonic splice may also exhibit a different gloss, an experienced projectionist should be able to easily find the reel changes on a platter just by looking at it. | These methods of marking reel changes are completely unnecessary for two reasons. First, platter houses used colorful [[splicing tape|zebra tape]] to delineate reel changes, so a projectionist rewinding at a responsible speed would be able to find the splice without an issue. Second, reel changes are visible on the platter. The splices themselves can usually be found (they are thicker than the surrounding film), and it is possible to differentiate between reels because the surface of each reel has a slightly different gloss (just as trailers joined on a reel can be distinguished by viewing the side of the reel). Although film that was printed separately and joined with an ultrasonic splice may also exhibit a different gloss, an experienced projectionist should be able to easily find the reel changes on a platter just by looking at it. | ||

At the extreme, some | At the extreme, some projectionists would scratch frame lines or even etch notes into the picture area. Others applied stickers to the picture area or wrote the reel number in Sharpie or grease pencil. It is also very common to find Sharpie tick marks that were applied to count frames at reel changes. These sources of print damage are the result of poor practices and are not an inherent flaw of large-reel transport systems. | ||

Despite these systems for marking reel changes, some projectionists working with platters or other large-reel transport systems were careless or intentionally negligent when breaking down prints. In the worst cases, the projectionist would ignore the original reel breaks and simply wind the film onto each reel until it was full and then make a new cut in the middle of the reel. This often went uncorrected at future venues. Even reel-to-reel theaters would often recue the poorly cut reels instead of restoring the original reel breaks. | Despite these systems for marking reel changes, some projectionists working with platters or other large-reel transport systems were careless or intentionally negligent when breaking down prints. In the worst cases, the projectionist would ignore the original reel breaks and simply wind the film onto each reel until it was full and then make a new cut in the middle of the reel. This often went uncorrected at future venues. Even reel-to-reel theaters would often recue the poorly cut reels instead of restoring the original reel breaks. | ||

Another source of intentional print damage is the application of the [[foil cues|foil cue tape]] required by | Another source of intentional print damage is the application of the [[foil cues|foil cue tape]] required by automation systems. Aluminized mylar tape was applied as strips or small circles, and the reflective surface triggered a sensor as it passed through the projector. Strip cues are particularly problematic because they take up more surface area and can be more difficult to remove, and when they are removed they can leave significant adhesive residue. Cues within the picture area are also visible on screen. Dot cues are less problematic because they take up less surface area (in 1.85 prints they could even be hidden by placing them in the cropped portion of the frame) and are easier to remove without damaging the print. In addition to foil cues, alternative systems were designed using barcodes stickers, but these were only employed on a large scale but the United Artists theater chain. These stickers were applied to the center of the frame and were very difficult to remove without damaging the print. Thoughtful projectionists would apply clear splicing tape beneath the cues so that they could be peeled off with less risk of scratching the picture area. | ||

<gallery widths=300px heights=300px mode=packed> | <gallery widths=300px heights=300px mode=packed> | ||

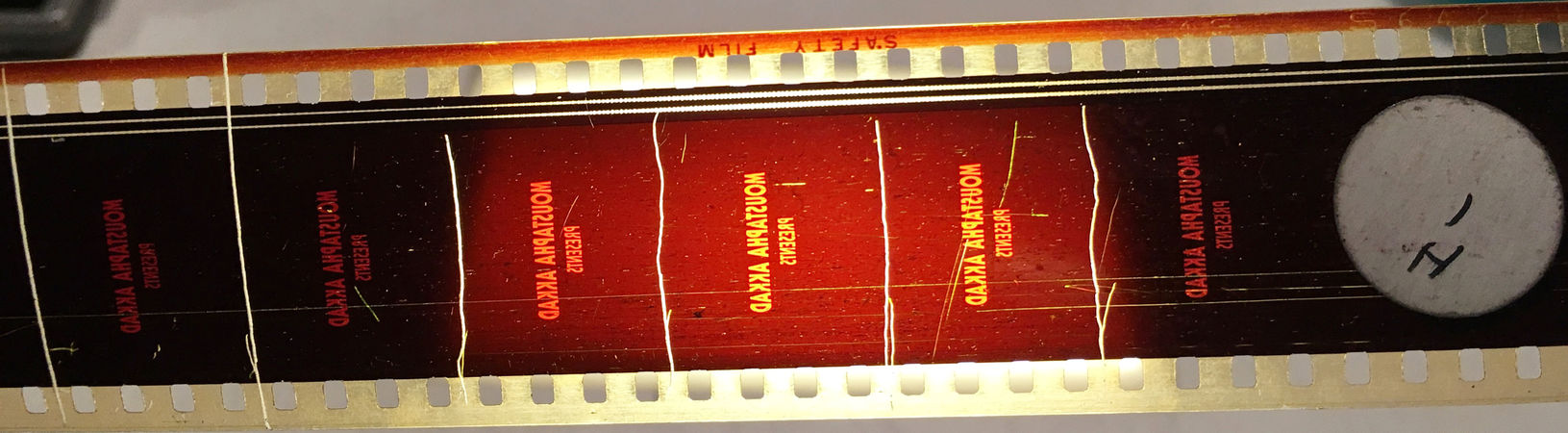

File:ScratchedFrameLine Halloween.JPG| | File:ScratchedFrameLine Halloween.JPG|The head of a film with intentional damage. Frame lines are scratched into the emulsion, and the scratches extend into the soundtrack. A sticker in the picture area identifies the reel. | ||

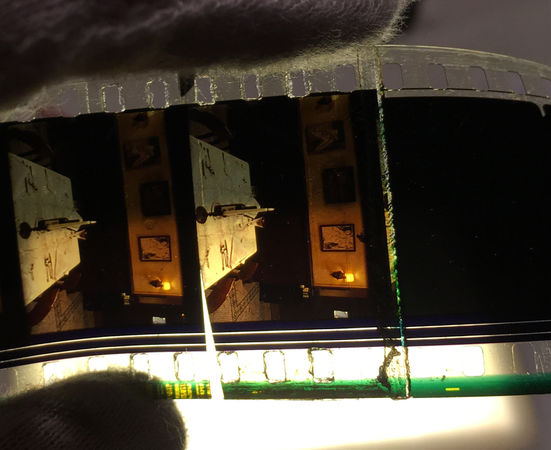

File:Platter splice.JPG| | File:Platter splice.JPG|Repeated cutting and splicing of heads and tails when plattering prints may lead to poorly cut frames or damaged perfs. | ||

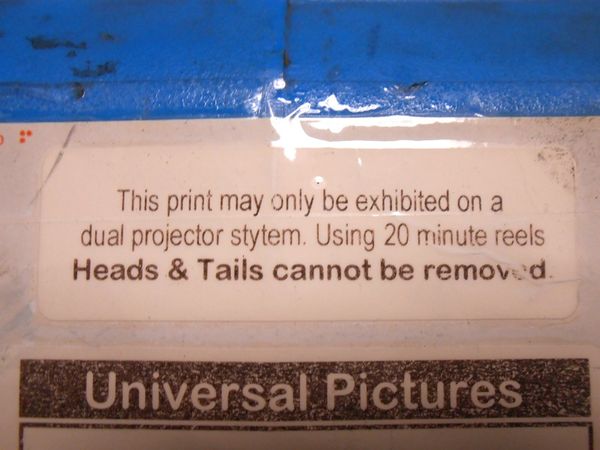

File:Universalplatterwarning.jpg | File:Universalplatterwarning.jpg| A note on an [[Archival prints|archival print]] from Universal prohibiting plattering. | ||

</gallery> | </gallery> | ||

===Makeup and Breakdown=== | ===Makeup and Breakdown=== | ||

Much of the damage to plattered prints occurs when individual reels are built up to the platter or when the print is broken back down to shipping reels. | Much of the damage to plattered prints occurs when individual reels are built up to the platter or when the print is broken back down to shipping reels. | ||

| Line 45: | Line 47: | ||

Another risk inherent to plattering and other large-reel systems is the damage caused by the equipment used to build up and break down prints. Large reels ranging from 6,000’ to 12,000’ were used for plattering, requiring greater holdback tension, which in combination with the rewind speeds commonly employed in platter houses often resulted in print damage. Most make-up tables were also problematic from a film handling perspective. This was compounded by careless projectionists, who would fail to properly align the make-up table to the platter, resulting in platter scratches; fail to regulate feed and takeup tension, especially during breakdown (when disengaged from their drive motors to feed out to the make-up table, many platters were freewheeling and friction had to be applied by hand to regulate the tension); wind the film at excessive speeds and start and stop abruptly; leave the equipment unattended during transport, etc. | Another risk inherent to plattering and other large-reel systems is the damage caused by the equipment used to build up and break down prints. Large reels ranging from 6,000’ to 12,000’ were used for plattering, requiring greater holdback tension, which in combination with the rewind speeds commonly employed in platter houses often resulted in print damage. Most make-up tables were also problematic from a film handling perspective. This was compounded by careless projectionists, who would fail to properly align the make-up table to the platter, resulting in platter scratches; fail to regulate feed and takeup tension, especially during breakdown (when disengaged from their drive motors to feed out to the make-up table, many platters were freewheeling and friction had to be applied by hand to regulate the tension); wind the film at excessive speeds and start and stop abruptly; leave the equipment unattended during transport, etc. | ||

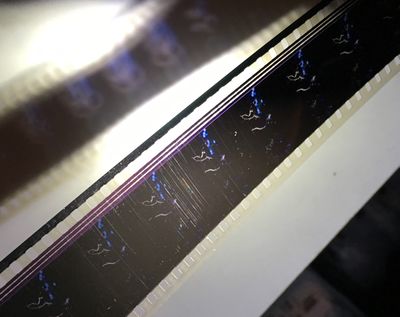

[[File:Plattermarks.jpg|right|thumb|400px|An example of "platter marks" on the emulsion side of a 35mm print, crossing into the optical track.]] | |||

What are often referred to as "platter marks" can occur when the picture area makes contact with the surface of the platter. This usually happens when the film is run to or from the platter using a make-up table. If the guide roller on the make-up table is too low, the lower side of the frame will drag across the platter as it spools. This typically results in slightly diagonal horizontal scratches that run from the film edge of one side, with the scratches ending partway way across the frame. Platter scratches can occur on the base or the emulsion side, depending on how the film is being spooled when the damage occurs. | |||

Kinoton make-up tables were generally much gentler on film than the other models available, using a simpler film path that required less handling of the picture area and employing Hall sensors to auto-calibrate the speed of the takup platter and perfectly regulate the film tension. However, the magnetic field generated by the Hall sensor will destroy a print with a magnetic soundtrack. | Kinoton make-up tables were generally much gentler on film than the other models available, using a simpler film path that required less handling of the picture area and employing Hall sensors to auto-calibrate the speed of the takup platter and perfectly regulate the film tension. However, the magnetic field generated by the Hall sensor will destroy a print with a magnetic soundtrack. | ||

Latest revision as of 17:44, 29 May 2020

A platter system is a non-rewind film transport system in which multiple reels are spliced together on a horizontal deck. Each platter deck can hold enough film to allow all but the longest features to play without a changeover or intermission. The film is fed through a centerfeed, run through the projector, and wound onto a center ring on the takeup platter. To play the film again, the ring is removed and the film is rethreaded through the centerfeed, allowing it to be run repeatedly without being rewound.

History and Use

Platter systems rose to popularity in the late 1970s as part of the movement towards increased automation. Along with the transition from carbon arc to xenon lamps and the development of automation control systems, platter systems facilitated the rise of the multiplex (a movie theater with several screens). Platter systems and other single-reel film transport systems such as towers and double make-up tables (MUTs) largely replaced reel-to-reel projection as the most common means of 35mm projection because it enabled the simultaneous screening of multiple films on multiple screens with fewer operators. Benefits of the platter system included reduced labor costs—multiple films could be run simultaneously by a single projectionist or theater manager—and reduced print wear over the course of a long run. After the reels have been plattered the projectionist only handles the clear leader spliced to the head and the tail of the last reel, and the print does not have to be rewound between each screening.

The same incentives also led most of the theaters that continued to use reel-to-reel projection for first-run exhibition to employ large-reel changeover systems, in which a feature was built up onto 6,000’ reels and a cue detection system was used to automate the changeover. Some large-reel changeover systems employed projectors that could rewind the reel through the projector mechanism after playback (so-called “rock-and-roll” projectors), providing a level of automation on par with a platter system.

Archival Implications

When properly maintained and operated by a skilled projectionist, platter systems can be a suitable method of projecting first-run films. However, from the 2010s onward the standard for exhibition began to move from 35mm prints and film projection to Digital Cinema Packages (DCPs) and digital projection. Although some theaters maintained the ability to screen film or have even added film projectors after digital became the industry standard (see:List of analog film exhibitors), the need for platter systems and automation greatly decreased because the frequency of screenings on film declined precipitously. Platter systems were designed to facilitate a theater's ability to screen prints multiple times a day, seven days a week, on multiple screens. Since the transition to DCP as the primary means of film distribution, platter systems have become obsolete (and unnecessary) in most situations Venues that continue to project film tend to do so with a frequency that is more compatible with reel-to-reel changeover projection systems.

Plattering introduces certain inherent risks to the condition of a film print, but many of the problems associated with plattering relate to poor practices, negligence, and more broadly the prioritization of business interests over good film handling practices and the deprofessionalization of projection as a trade.

In addition, plattering or otherwise building up prints for large-reel playback is not considered acceptable for archival film prints. Film archives and the repertory divisions of many studios and distributors now strictly forbid plattering or building 35mm prints up to reels larger than 2,000 feet. If a theater wishes to borrow prints from these sources they can only do so if they have a changeover system.

While platter systems are often singled out as uniquely problematic by lending institutions, there are also a number of equipment-related concerns related to reel-to-reel projection which are not as stigmatized as platter systems but are just as problematic. For example, some changeover houses still use outdated single-speed motorized rewinds that cinch the film on every rewind, and some legacy installations use overpowered lamps without adequate cooling, resulting in heat damage to every print they run.

Damage Associated with Plattering

Intentional Film Damage

Much of the damage associated with plattering and large-reel projection is intentionally inflicted by projectionists as part of their regular workflow.

Most intentional damage is related to the marking of reel changes. The most common method of marking reel changes was to apply shoe polish or white paint pen to the film edge in the vicinity of the reel change so that it would be easily visible during breakdown. This results in print contamination, dirt buildup in the projector, and when poorly applied can cover the soundtrack and even run into the picture area. A less destructive method of marking reel changes employed yellow adhesive roll tape, which was folded over the film edge. When poorly applied, this tape could run past the film edge or cover a portion of the perforations and the Dolby Digital soundtrack.

These methods of marking reel changes are completely unnecessary for two reasons. First, platter houses used colorful zebra tape to delineate reel changes, so a projectionist rewinding at a responsible speed would be able to find the splice without an issue. Second, reel changes are visible on the platter. The splices themselves can usually be found (they are thicker than the surrounding film), and it is possible to differentiate between reels because the surface of each reel has a slightly different gloss (just as trailers joined on a reel can be distinguished by viewing the side of the reel). Although film that was printed separately and joined with an ultrasonic splice may also exhibit a different gloss, an experienced projectionist should be able to easily find the reel changes on a platter just by looking at it.

At the extreme, some projectionists would scratch frame lines or even etch notes into the picture area. Others applied stickers to the picture area or wrote the reel number in Sharpie or grease pencil. It is also very common to find Sharpie tick marks that were applied to count frames at reel changes. These sources of print damage are the result of poor practices and are not an inherent flaw of large-reel transport systems.

Despite these systems for marking reel changes, some projectionists working with platters or other large-reel transport systems were careless or intentionally negligent when breaking down prints. In the worst cases, the projectionist would ignore the original reel breaks and simply wind the film onto each reel until it was full and then make a new cut in the middle of the reel. This often went uncorrected at future venues. Even reel-to-reel theaters would often recue the poorly cut reels instead of restoring the original reel breaks.

Another source of intentional print damage is the application of the foil cue tape required by automation systems. Aluminized mylar tape was applied as strips or small circles, and the reflective surface triggered a sensor as it passed through the projector. Strip cues are particularly problematic because they take up more surface area and can be more difficult to remove, and when they are removed they can leave significant adhesive residue. Cues within the picture area are also visible on screen. Dot cues are less problematic because they take up less surface area (in 1.85 prints they could even be hidden by placing them in the cropped portion of the frame) and are easier to remove without damaging the print. In addition to foil cues, alternative systems were designed using barcodes stickers, but these were only employed on a large scale but the United Artists theater chain. These stickers were applied to the center of the frame and were very difficult to remove without damaging the print. Thoughtful projectionists would apply clear splicing tape beneath the cues so that they could be peeled off with less risk of scratching the picture area.

-

The head of a film with intentional damage. Frame lines are scratched into the emulsion, and the scratches extend into the soundtrack. A sticker in the picture area identifies the reel.

-

Repeated cutting and splicing of heads and tails when plattering prints may lead to poorly cut frames or damaged perfs.

-

A note on an archival print from Universal prohibiting plattering.

Makeup and Breakdown

Much of the damage to plattered prints occurs when individual reels are built up to the platter or when the print is broken back down to shipping reels.

One problem that is always present when plattering or building up to large reels is the need to cut the head and tail off of each reel in order to join the reels together. To prevent the reel order from being mixed up when the print is broken down, the first and last frame of picture were left on the head and tail respectively. This identifying frame (sometimes called a match frame) was then matched to the reel upon breakdown. If done properly, this results in a single splice (probably concealed by the changeover when run reel-to-reel) and no footage loss. In practice, however, it was common for projectionists to tear the tape splices between the reels by hand instead of peeling off the tape, causing damage to the frames. It was also common practice for each subsequent venue to simply make a fresh cut instead of reusing the existing head or tail splice. This resulted in cumulative footage loss, and often in a series of poorly made splices immediately adjacent to one another at the end of the reel. Heads and tails were often rejoined to the reel using masking tape instead of being properly spliced.

Regardless of the technique employed, cutting and rejoining the heads and tails also led to increased handling of the picture area. At the very least, the picture area was handled in order to splice the reels together and subsequently break them apart (usually without gloves), but due to the overall rough handling of film prints in platter houses, this also meant that the picture area would often come into contact with the floor or meet some other form of abuse. It also frequently led to mishandling of the heads and tails, resulting in print contamination. As a result, plattered prints were often badly scratched and filthy at the reel changes.

Another risk inherent to plattering and other large-reel systems is the damage caused by the equipment used to build up and break down prints. Large reels ranging from 6,000’ to 12,000’ were used for plattering, requiring greater holdback tension, which in combination with the rewind speeds commonly employed in platter houses often resulted in print damage. Most make-up tables were also problematic from a film handling perspective. This was compounded by careless projectionists, who would fail to properly align the make-up table to the platter, resulting in platter scratches; fail to regulate feed and takeup tension, especially during breakdown (when disengaged from their drive motors to feed out to the make-up table, many platters were freewheeling and friction had to be applied by hand to regulate the tension); wind the film at excessive speeds and start and stop abruptly; leave the equipment unattended during transport, etc.

What are often referred to as "platter marks" can occur when the picture area makes contact with the surface of the platter. This usually happens when the film is run to or from the platter using a make-up table. If the guide roller on the make-up table is too low, the lower side of the frame will drag across the platter as it spools. This typically results in slightly diagonal horizontal scratches that run from the film edge of one side, with the scratches ending partway way across the frame. Platter scratches can occur on the base or the emulsion side, depending on how the film is being spooled when the damage occurs.

Kinoton make-up tables were generally much gentler on film than the other models available, using a simpler film path that required less handling of the picture area and employing Hall sensors to auto-calibrate the speed of the takup platter and perfectly regulate the film tension. However, the magnetic field generated by the Hall sensor will destroy a print with a magnetic soundtrack.

Plattering and large-reel projection also pose additional concerns when running aging acetate, especially if it’s beginning to exhibit symptoms of vinegar syndrome. Acetate experiencing rigidity or edgewave is always difficult to spool evenly, but at larger circumferences it is more prone to slip or fold over itself, causing kinks and S bends. Aging acetate that is experiencing these sorts of structural issues can also fail to spool evenly to the platter during playback. Instead, it will telescope up and lift off the platter with each successive rotation, a problem known as pyramiding. Without a dedicated projectionist to guide the film by hand if pyramiding occurs, this can lead to disaster. Furthermore, some failsafes designed for platter systems cannot accommodate old-school film repairs and therefore have to be bypassed to protect the film. For example, a notch repair can cause the roller arms on a Kelmar failsafe to drop, resulting in a film break.

Projection Failures

Platter systems were usually fully automated, creating a financial incentive to understaff projection booths and leave projectors unattended while in operation. This made projection failures of all kinds more likely, since projectionists were not provided with enough time to double check their work and nobody was present to catch a problem when it occurred. To make matters worse, a simple error such as a misthread could damage the entire film print in one pass, instead of only affecting one reel.

There are also sources of print damage that are unique to platter systems. These include:

- Brain wraps: Film can wrap around the centerfeed (commonly called the “brain”), preventing it from advancing. When a brain wrap occurs, the portion of the film engaged with the sprockets is mangled and the film in the gate will blister or burn unless the dowser is closed immediately. Brain wraps can be caused by disengaged feed platters, problems with the centerfeed, sticky film, tape left on the tail, and static build-up in polyester film.

- Platter fling: Film can be thrown from the platter during playback. This can be caused by a poorly timed platter motor, a poorly secured tail, a poorly leveled platter deck, or simply because the film on the feed platter loses its circular form and becomes unbalanced towards the end of the show. Some theaters used retaining devices (ex., sticky retainers, suction cups, retention rings) to prevent platter fling.

- Film spills: Platter systems are prone to two sorts of film spill. Most commonly, the takeup platter is not properly engaged and the film is fed through the projector and then spilled onto the floor. Without film break sensors in place, an entire print can spill out if the projector is unattended. Film can also spill off of the feed platter if the tail becomes loose. The tail cannot be secured with tape, which would cause a brain wrap, so it is generally just tucked underneath the print. If the projectionist forgets to tuck it in or it comes loose during playback, it can slip off the edge of the platter and cause a cascading film spill.

- Endless loop systems: While primarily used for specialized installations such as museum exhibits, endless loop platters were popular in multiplexes for a brief period. These systems have a number of issues, including the fact that the film accumulates dirt more quickly because the projector cannot be properly cleaned. Film run through an endless loop also eventually develops mottling from repeated film-on-film contact, and some models have swinging guide arms that scratch the film. The many issues associated with endless loops were exacerbated by the transition to polyester film in the 1990s. Polyester is susceptible to static cling unless the temperature and humidity of the booth are carefully maintained, and this can prevent the film from feeding correctly. While this is an issue with all platter systems, it is especially problematic for endless loops, which require the film to be loosely packed.

Film Transport Concerns

In addition to concerns related to building prints to a single platter, platter houses also employed potentially dangerous methods of transporting film between auditoriums. During regular operation, platter systems also expose more film during transport than reel-to-reel systems, exposing them to dust and dirt.

Problematic transport methods include:

- Film clamps: Clamps were placed around the film on one platter deck and used to pick it up and carry it to another platter or to a temporary storage location (for a careless projectionist, this might mean the floor). If the clamps were not properly secured or the feature was either too long or too short to safely clamp it, the disk of film would be unstable and could even fall out of the clamps. It was safest to move heavy prints as a team, and a single projectionist attempting to move a print by themself might drop it. This risk was even greater when an insufficient number of clamps were used to secure the film, or the clamps were not evenly spaced. Clamps were designed to move a print with the center ring attached, but some projectionists would remove the ring before clamping, making the print unstable and causing cinch scratching.

- Platter boards: A thin board or metal sheet is placed on the takeup platter. After the film has played, it can be lifted up by the support beneath it and carried. As with film clamps, this presents a risk of dropping the print.

- Modular platter reels: Perhaps the safest method of carrying an entire print, the film was taken up to a 12,000’ split reel. When running to the reel, the bottom flange and core were placed on the platter, and the film was wound to the core upon playback. The tail was then taped down and the upper flange was reattached so that the film could be safely transported. Due to the added weight of the metal split reel, there was a risk of dropping the print if one projectionist attempted to move it by themself.

- Interlocking: It was a common practice in multiplexes to run a single print between multiple projectors at the same time, a practice known as interlocking. This resulted in a convoluted film path and presented projector synchronization issues, increasing the risk of print damage.

Benefits of Platter Systems

Despite the numerous problems associated with platter systems, they compare favorably to reel-to-reel systems in some regards.

Most importantly, a platter system provides perfectly even feed and takeup tension because the platter rotation speed changes during playback. In this regard they are superior to the feed and takeup frictions on purely mechanical reel-to-reel projectors, which are often the source of major print damage. While platters do require maintenance to ensure proper feed and takeup (ex., platter motor timing must be calibrated), under typical operating conditions reel-to-reel systems require more regular maintenance and and calibration to prevent print damage. One inherent problem with purely mechanical reel-to-reel projectors is that the feed and takeup tension must be fixed, despite the fact that the optimal tension fluctuates as the reel diameter changes over the course of playback (a reel with less film on it requires less holdback tension than a reel with more film on it). Tension must also be adjusted between reels of different capacities and hub sizes, and when running film of different gauges on a dual format projector. The clutch components also wear over time, requiring recalibration. This does not apply to reel-to-reel projectors with auto-calibrating frictions such as the Kinoton E series.

For long runs, platter systems also reduce the overall handling of the film. If the projectionist wears gloves and takes care to avoid surface contact and print contamination when building up and breaking down the print, many problems typically associated with plattering may be avoided. Platter covers can also be used to protect the print from dust when not in use.

For these reasons, platter systems remain an acceptable transport method for newly struck 70mm prints. With the revival of 70mm as a prestige format in the 2010s, a new print assembly workflow was developed for platter houses. For the 70mm releases of Hateful Eight and Dunkirk, the onus of cleanly assembling the prints was taken off of the individual projectionist. Instead, Boston Light & Sound created a “platter farm” where the 1,000’ reels were preassembled using ultrasonic splicers and shipped on modular platter reels to each venue.[1][2]

References

- Bordwell, David. “The Hateful Eight: The boys behind the booth.” Observations on film art (blog), December 5, 2015. Accessed February 9, 2019. http://www.davidbordwell.net/blog/2015/12/05/the-hateful-eight-the-boys-behind-the-booth/.

- Boston Light & Sound. “Dunkirk Premiere: BL&S helps revive Super Panavision 70 for projecting Christopher Nolan’s visionary WWII film.” Press release, 2017. Accessed February 9, 2019. http://www.blsi.com/portfolio_70mm_film_engagements.php#portfolioOneAnchor.